Richard Nixon

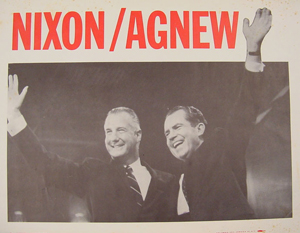

Nixon and Agnew campaign poster from 1968.

Courtesy Hudson Library and Historical Society

When the general election season opened in September 1968, Nixon promised he'd say nothing about President Johnson's peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese. He said he didn't want to interfere with the peace process. Nixon, in fact, tried not to say much of anything of substance. He was leading Humphrey in the polls by double-digits; the less he said the better.

Historian Dan Carter says "even by the standards of modern campaign rhetoric," Richard Nixon's stump speeches "were stultifyingly vacuous."

Kevin Phillips, a Nixon campaign advisor in 1968, says one of the weakest things about Nixon's campaign, "was the way he could come up with clichés, and they all had to do with law and order." Phillips urged Nixon to make a strong indictment of failed liberal policies, but Nixon preferred to speak in hazy generalities.

This allowed Nixon to remain vague - at times even contradictory - about politically charged topics like school busing. Nixon knew he couldn't win the Deep South over former Alabama Governor George Wallace, who was running as a third-party candidate. Nixon wooed white southern voters nonetheless. Nixon got the crucial support of Strom Thurmond, a powerful senator from South Carolina who had switched his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican in 1964. Nixon won over Thurmond with promises to use a light presidential touch on enforcing school desegregation. Nixon also named a conservative running mate - Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew - one of the people Strom Thurmond had privately listed as an acceptable pick.

Critics accused Nixon of pandering to Wallace voters, but in a conversation with reporters on Face the Nation a week before the election, Nixon drew a careful line between himself and the race-baiting Alabaman. Nixon said he was against busing, but "I am [also] against segregation." While federal funds should not be used to force integration through busing, Nixon said, "No funds should be given to a district which practices segregation."

By the end of October, Humphrey and Nixon were running neck and neck. On October 31, Nixon staged a televised rally at Madison Square Garden in New York. He said he'd been careful not to insult his opponent, but since he was in a sports arena, "this is the time … to take off the gloves and sock it to him."

Earlier that day, President Lyndon Johnson had announced a halt in the bombing against North Vietnam. Nixon promised once again to keep silent about Johnson's peace initiatives. "We won't say anything that might destroy peace; we want peace in America." Still, Nixon said, whatever the outcome of LBJ's attempts to forge peace, the nation needed new foreign policy. "There isn't a place in the world where the United States isn't worse off than it was eight years ago," Nixon said. As president, Nixon would "defuse trouble spots and negotiate where we need to. We shall have peace," he promised.

While Nixon kept quiet in public about Vietnam, he was secretly using back channels to sabotage the peace process. Through a well-placed representative, Nixon told South Vietnamese allies that if they held out for peace until after the election he would give them a better deal than Lyndon Johnson.

It may have been a dirty ploy to win the election, but Nixon believed it was fair play. Rick Perlstein says Nixon saw Johnson's bombing halt as an attempt to steal the election for Hubert Humphrey. "Nixon always thought he was playing defense," Perlstein says.

Richard Nixon announces his victory at the Waldorf-Astoria on November 5th, 1968.

Video courtesy RealAgentOfSHIELD

On November 5, 1968, Nixon watched the election returns from a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. It was a long, tense night. The networks did not announce his victory until the next morning.

After Humphrey conceded the race that morning, Nixon went down to the hotel ballroom where a large crowd of supporters was waiting. It was just after noon. He was accompanied by his staff, secret service members and his family. "Ladies and Gentlemen," he joked, "I didn't realize so many of you would stay up so late."

Nixon told the crowd about a telephone conversation with Humphrey earlier that day. "I congratulated him for his gallant and courageous fight against great odds," Nixon said. "I also told him that, as he finished this campaign, that I know exactly how he felt. I know how it feels to lose a close one."

The crowd laughed and Nixon beamed.

Nixon continued, "I can say this: Winning's a lot more fun!"

Nixon's final margin of victory over Hubert Humphrey was small, but political analysts believe it would have been much bigger had George Wallace stayed out of the race. While Wallace drained some votes from Humphrey, he siphoned off even more from Richard Nixon. Ultimately, the 1968 election results were a "landslide for the backlash against liberalism," Perlstein says.

Nixon would ride that backlash to a genuine electoral landslide in 1972, with a crushing reelection victory over liberal Democrat George McGovern.

Return to Campaign '68