George C. Wallace

Powerful Third-Party Candidate

part 1, 2

George C. Wallace

Courtesy the National Archives and Records Administration

George C. Wallace was a powerful loser. Running as an independent, Wallace came in a distant third in the 1968 presidential election. But it was still much closer than expected. Wallace was scorned and repudiated by many mainstream voters, but he appealed to a critical wedge of the electorate. His 1968 bid for the presidency - and his skillful use of that wedge - helped split open American politics for the rest of the 20th century.

Like no candidate before, Wallace harvested the anger of white Americans who resented the progressive changes of the 1960s. Wallace supporters feared the urban violence they saw exploding on television. With tough talk and a rough-hewn manner, Wallace inspired millions of conservative Democrats to break from their party.

For many of them, the separation was permanent. Wallace Democrats would later become known as Reagan Democrats.

George Wallace was one of the most notorious segregationists of the 1960s. In his first speech as Alabama governor in 1963, he promised his supporters, "Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!" So when Wallace announced he was running for president in 1968, most pundits and politicians dismissed him as a fringe candidate. To them, Wallace was a regional candidate who was profoundly out of step with the march of racial progress that had taken place in the United States since he first became governor.

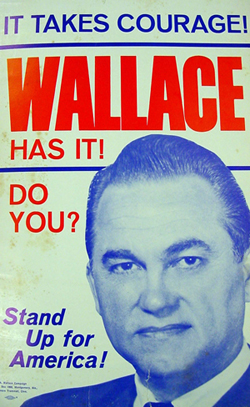

A campaign poster for George C. Wallace urging voters to "Stand up for America!"

Courtesy the Hudson Library and Historical Society

But in 1968 Wallace wasn't talking to voters who embraced civil rights and anti-poverty programs. He appealed to white Americans who felt abandoned by their government. And he found them not just in the South, but also parts of Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana and other northern states. According to historian Michael Kazin, these were voters who "felt their good jobs, their modest homes, and their personal safety were under siege both from liberal authorities above and angry minorities below."

Wallace was "an extraordinarily intuitive politician," says Wallace biographer Dan T. Carter. "He understood that even at the height of the Great Society [Lyndon Johnson's sweeping domestic reform program] and the civil rights movement, there were tens of millions of Americans who really were not supportive of the kind of social changes that were taking place in the United States."

In 1968, student radicals, anti-war protestors and violent black activists were grabbing the headlines. Carter says Wallace knew that many whites despised these people as symbols of "a fundamental decline in the traditional cultural compass of God, family, and country."

Wallace relished confronting the left-wing protesters who stalked his campaign rallies. When a heckler interrupted him, Wallace would respond: "Son, if you'll just shut up and take off your sandals, I'll autograph one as a souvenir." Unlike Humphrey and Nixon, Wallace wanted these hecklers in his audience. Bearded peaceniks were just the kind of opponents he wanted viewers to see on TV.

Wallace often posed as the candidate of the forgotten man. He encouraged his supporters to resent the major parties, their candidates, and the established power structures in the United States (especially news media and academic types). "Yes, they've looked down their nose at you and me a long time," Wallace would declare. "They've called us rednecks … Well we're going to show Mr. Nixon and Mr. Humphrey that there sure are a lot of rednecks in this country!"

The angry fervor of Wallace rallies frequently led to fistfights and bloodshed. People who loved Wallace and the people who hated him beat each other up. The brawling got to be so common that television crews covering Wallace set up two cameras, one to face Wallace and one to capture the melee in the crowd.

The violence stopped there, but some supporters wanted more. In an interview with historian Dan Carter in 1988, Wallace aide Tom Turnipseed recalled meeting a group of Polish-Americans at a local bar in Massachusetts. "Now let's get serious a minute," said one of the men. "When George Wallace is elected president, he's going to round up all the niggers and shoot them, right?" Turnipseed laughed and said, "Naw, we're not going to shoot anybody." The man gave Turnipseed a hard look. "This guy got pissed," Turnipseed said, "and he said, 'Well, I don't know whether I'm for him or not.'"

Wallace never spoke directly about race in his campaign, but it was at the core of his message. Civil rights laws passed in the 1960s forcing desegregation in the South extended to every other part of the country. Once considered a distinctly southern problem, whites outside the South realized that they, too, would have to make a place in their schools, neighborhoods and work places for black people. They didn't like it.

Wallace spoke in a coded language that his listeners easily understood. "Wallace constantly talked about defending the integrity of neighborhoods and neighborhood schools," Carter says, "[knowing] that everyone was aware he was talking about white neighborhoods, or defending white schools." At a campaign stop in Houston, Wallace got huge applause for an attack on busing.

Wallace was quick to say he was not a racist. As evidence, he offered his wife, Lurleen. She won the race for governor in 1966 and got most of the black vote. (Lurleen Wallace ran as a surrogate for her husband when he reached Alabama's one-term limit; George Wallace ran the state from off-stage.) Though Wallace insisted his wife was popular with blacks, critics said Lurleen Wallace was simply the least-offensive segregationist on the ballot.

By late September of 1968, election polls showed Wallace with 21 percent of the vote. Wallace's campaign was well-funded, but he was also helped by the fact that he got a lot of free press. "He had this ability to seize upon issues to capture public attention," Dan Carter says. "And very quickly newspaper reporters and the broadcast media realized that he was good copy." Many professional commentators derided Wallace (Tom Wicker of the New York Times referred to him as "the Alabama demagogue"), but still he appeared frequently on major television news shows.

Continue to part 2