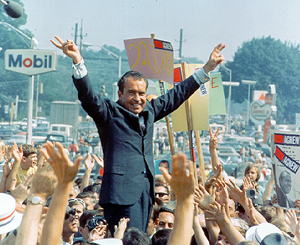

Richard Nixon

Nixon gives his trademark "victory" sign while campaigning in Philadelphia, July 1968.

Photo by Ollie Atkins

Nixon got to the Miami convention by running one of the most sophisticated campaign operations in American history. At the center of it was a team of top-flight ad men and television producers who figured out how to sell Nixon to the public. In a television interview early in the campaign Nixon said, "Nobody's going to package me. Nobody's going to make me put on an act for television." But, with Nixon's blessing, that's exactly what they did.

A central architect of Nixon's television campaign was a young producer for the Mike Douglas Show, Roger Ailes. Nixon met Ailes when he was a guest on the show in 1967. Sitting in a make-up chair, Nixon said it was silly to have to go on TV to get elected president. According to Rick Perlstein, Ailes' response was a surprise. "Mr. Nixon," Ailes said, "if you think this is silly you'll never become president of the United States." Nixon liked the young prodigy and put Ailes on the payroll. (Ailes later played a crucial role in the campaigns of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, and went on to become the head of Fox News.)

Nixon's media team scrutinized their candidate's earlier television appearances and agreed Nixon came off best in more informal settings, places where he could speak extemporaneously. So they began to stage artificial town hall meetings - called "Man in the Arena" - where Nixon would take questions from a handpicked crowd of supporters. The idea was to destroy the image of Nixon as a loser by showing him as a fighter, someone who could survive tough questions on the public stage.

In one exchange a black man asks Nixon whether the candidate's call for "law and order" has a different meaning for black Americans demanding equality than for white bigots who have "slaughtered, murdered, maimed" black people all over the South. Nixon defends his use of the term. "I don't go along with people that say law and order is a code word for racism," Nixon says. Minorities should be especially concerned about law and order because, he says, "if you have mob rule, eventually the majority's mob will rule and the minority will have no rights at all."

Nixon concludes with one of his stock lines, "Law and order is in the interest of all Americans. Let's just make sure that our laws deserve respect; then, they will be respected by all Americans." The crowd erupts in applause.

Nixon campaign ad: "Today a violent crime is committed every 60 seconds."

Video courtesy drerxn

Journalist Tom Wicker covered Nixon's campaign for the New York Times. In his book, One of Us: Richard Nixon and the American Dream, Wicker writes that these televised exchanges were a "masterly new political concept." They enabled Nixon to appear as if he were being questioned freely, "while running little risk of a hostile inquiry, a damaging answer or some other mistake."

Nixon used television in another crucial way: As a substitute for personal appearances. Nixon realized he could reach more voters via TV than on the stump. So he held just one or two rallies a day. Each rally was held near an airport so that television crews could whisk the film off to New York in time for the evening news.

Meanwhile, Nixon's Democratic opponent, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, campaigned nonstop. Humphrey would hold a dozen rallies a day. On the news every night, Rick Perlstein says, "You would see two images from the campaign: The one gaffe that Hubert Humphrey had made at his 10 or 12 or 15 rallies during the day, and the perfectly rehearsed, perfectly fresh talking points of the Nixon campaign."

Nixon campaign ad: Nixon for American youth

Video courtesy rfkmustdie

Some analysts say Nixon revolutionized the use of television for presidential campaigning. Others caution there was nothing especially new about Nixon's techniques and tactics. What Nixon had that was different, says historian Dan T. Carter, "was a new level of professional sophistication and vast resources."

Nixon's budget dwarfed Humphrey's and much of it was spent on advertising. Few commercials show pictures of Nixon himself (Nixon's media team felt it was difficult to make him appear likable). Instead, they feature spare voice-over narration and vivid images that tell a story. In one ad, the camera trails a tense, matronly white woman walking on an empty street at night while an announcer itemizes disturbing crime statistics. Another features still photographs of wounded soldiers and frightened civilians in Vietnam. This time Nixon narrates the ad. "Never before has so much power been used so ineffectively as in Vietnam," he says. Nixon vows he will bring an honorable end to the war.

In most of his stump speeches, Nixon cast the 1968 election as the one that would determine whether or not peace and freedom would prevail in the world. His advertising campaign underscored this idea with a slogan or caption that appeared at the end of commercials: "This time vote like your whole world depended on it."

Nixon's vast resources were also used to manage the press. Nixon's handlers kept him away from reporters. The ones traveling with Nixon only got quick two-minute interviews as Nixon's airplane was landing. Sequestered from the man they were trying to cover, reporters were fed copious amounts of food and booze. A British journalist covering Nixon's campaign observed that the press corps "fell into a state of what one can only call astounded torpor."

Continue to part 3