Hubert H. Humphrey

Humphrey and Lyndon Johnson. Humphrey's role as vice president in the Johnson administration made differentiating his positions difficult.

Courtesy Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

Humphrey's message on Vietnam was a difficult sell to anti-war Democrats. He had been supporting Johnson's escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam for years. "I was very, very angry at Hubert Humphrey," says historian Sara Evans. She was active in both the women's liberation and anti-war movements. "I was disillusioned because Humphrey had supported the war - he said what Johnson told him to say. I felt like I didn't have a candidate who represented me."

Humphrey knew he needed to differentiate himself from the president. But he had trouble doing it. In a question-and-answer session at Kent State, Humphrey said it was his duty to support administration policy. He might be a candidate, but he was still Johnson's number-two man. "The vice president of the United States is one of the president's advisors," Humphrey explained. "He is not president. And that's the first thing he needs to learn."

That was a message Johnson never let Humphrey forget. More than once Humphrey gingerly approached the president for permission to offer his own peace plan to voters. Each time, Johnson smacked him down. In private conversations, Johnson was distraught at how Vietnam had poisoned his presidency. He viewed anyone who opposed him as a traitor.

"Humphrey was under terrible pressure from Johnson and many of the Democratic Party leaders to continue to support Johnson in the war," says political reporter Al Eisele of The Hill newspaper. Eisele covered the 1968 campaign. "In his own mind, Humphrey understood that if he didn't separate himself from Johnson he'd have no chance of winning," Eisele says.

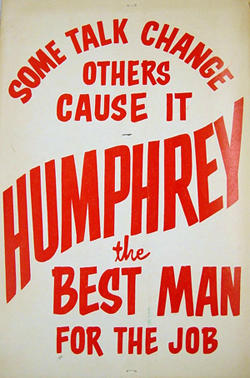

A campaign poster for Hubert Humphrey.

Courtesy Hudson Library and Historical Society

For Humphrey supporters, it would be a long wait before their candidate dealt firmly with the Vietnam issue. It was a delay that proved fatal to Humphrey's run for the White House.

After Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated on June 5, Humphrey was all but assured the party nomination. But the Democrats' late-August convention in Chicago would prove to be anything but a coronation. Eugene McCarthy did not have enough delegates to win the nomination, but he helped fuel a divisive platform fight on Vietnam that directly challenged the administration, and therefore Humphrey.

President Johnson didn't attend the convention. He pulled strings from off-stage to thwart the addition of a peace plank to the party platform. Bitter divisions over Vietnam were tearing the Democrats apart inside the convention hall. Meanwhile, anti-war groups from around the country had been planning for months to protest at the convention.

Thousands of hippies and peace activists arrived in Chicago. They came with diverse ideas of how to achieve peace and social justice. Some wanted to work within the political system, others dismissed the system as corrupt - an edifice to be torn down. Some suggested violence, some endorsed passive disobedience, some proposed mischief, such as lacing Chicago's water with LSD.

The city's mayor took them all seriously. To Richard J. Daley, they all looked the same. "These people are terrorists," Daley said on CBS. "They're against our party and against our government." The Democratic mayor used his extraordinary power over the machinery of government to foil the demonstrations. He promised to crack down hard on disorder or civil disobedience.

Violence flared on the first day of the convention, August 26. Over the coming days, police and National Guard troops used tear gas, clubs and rifle butts to battle the demonstrators, who denounced them as "fascists" and "pigs." Journalists got caught up in the street brawls. Chicago police inside the convention hall even roughed up prominent TV correspondents. It was a publicity disaster.

The drama came to a climax the evening Humphrey gave his nomination acceptance speech. Television coverage cut between convention business and street rioting. It all made for a devastating backdrop to what Democratic leaders had hoped would be their moment to show strength and unity.

"Democrats came to be perceived as divided, angry and in the midst of chaos," says former Humphrey aide Ted Van Dyk. "The nature of the convention didn't help in the fall election, of course."

Presidential candidates typically enjoy a bump in the polls coming out of their convention. Humphrey lost ground. After Chicago he trailed Nixon by 15 points. His campaign floundered. Fundraising sputtered. So the veteran campaigner did what he knew best: Humphrey hit the hustings hard. The vice president was an energetic speaker who hurtled through a daily schedule of rallies and speeches, often talking himself hoarse.

Continue to part 3