Robert F. Kennedy

The 82-Day Candidate

Contributing Photographer Steve Schapiro first covered Robert F. Kennedy in 1964, when Kennedy ran for the U.S. Senate in New York. In 1967 and 68, Schapiro photographed Kennedy at his home in suburban Washington DC and on the presidential campaign trail. The images are published in his new book, Schapiro's Heroes.

Slideshow music composed by Duke Levine

Robert F. Kennedy was a presidential candidate for just 82 days. In that brief time, his campaign reflected the passion and the peril of the 1968 race. Kennedy entered the contest primarily to challenge Lyndon Johnson's handling of the Vietnam War. But Kennedy's focus soon turned to domestic issues he'd long been concerned about: Poverty and racial inequality.

Kennedy jumped into the race for the Democratic nomination on March 16, 1968. It was four days after Senator Eugene McCarthy's surprisingly successful challenge of incumbent President Lyndon Johnson in the New Hampshire primary. Kennedy declared that America was on a "perilous course" - especially regarding the Vietnam War - and that he felt "obliged" to do all that he could to change that course. That included trying to unseat his own party's president.

McCarthy supporters blasted Kennedy as a ruthless opportunist who waited until their man made it safe to challenge Johnson before jumping into the race. Democratic Party heavyweights were livid at Kennedy for dividing the party. "I knew we were going to take a lot of flack," says Frank Mankiewicz, Kennedy's press secretary. "The party was already badly divided and the New Hampshire primary showed that."

The first campaign trip took Kennedy to Kansas. Kennedy worried that his anti-Vietnam message would get a cool reception in that historically conservative state. At a packed rally at Kansas State University, Kennedy said the nation's soul was deeply disturbed by Vietnam, that its moral position in the world was compromised. "Now is the time to stop," he declared.

Kennedy also confessed his own role in the Vietnam nightmare as Attorney General. He explained that when his brother, John F. Kennedy, was president, "I was involved in many of the early decisions on Vietnam, decisions which helped set us on our present path." He went on:

It may be the effort was doomed from the start … I am willing to bear my share of the responsibility, before history and before my fellow citizens. But past error is no excuse for its own perpetration. Tragedy is a tool for the living to gain wisdom, not a guide by which to live.

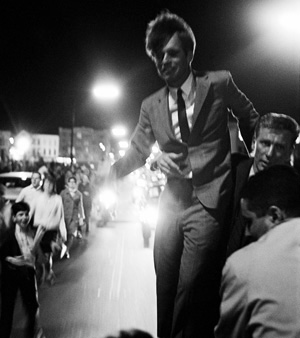

Robert F. Kennedy on the campaign trail.

Photo by Steve Shapiro

The college students in Kansas cheered and hollered and rushed the stage. They touched Kennedy's wavy brown hair and tore his shirtsleeves. "It was as if some force had been released that we hadn't counted on," Mankiewicz remembers. Thurston Clarke, author of a book on Kennedy's presidential bid titled The Last Campaign, says national reporters following Kennedy were surprised and excited by the rapturous reaction in Kansas. "The press was just stunned by what they'd seen," Clarke says. "One reporter said: 'I can't believe this! He's going all the way [to the White House]!' Finally, a reporter from Newsweek said, 'I'm not so sure we're going to like how this turns out'."

Talk that someone might want to assassinate a second Kennedy lingered throughout the campaign (John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Texas in 1963). When the issue was raised in private conversations, Kennedy usually brushed it off. But occasionally he brooded on the threat. When balloons popped or firecrackers exploded at campaign events, Kennedy sometimes visibly flinched.

Continue to part 2