Eugene McCarthy

part 1, 2

Eugene McCarthy at a press conference.

Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

On March 12, 1968, McCarthy stunned the nation - and the Johnson White House - when he came close to defeating the president in New Hampshire. The vote was 42 percent for McCarthy and 49 percent for LBJ.

Sandbook says McCarthy was as surprised as anyone by the outcome in New Hampshire. "He thought he'd raise the standard of the war in a few primaries and then that would be it," Sandbrook says. "He didn't realize how well he would do."

Political analysts would decide that voters in New Hampshire disliked Johnson more than they loved McCarthy.

"People were looking for almost any candidate who was saying almost anything different about the war," Sam Brown told an oral history interviewer a year after the election. Brown was the McCarthy campaign's national volunteer coordinator. "If someone had been up there saying, 'We ought to go in [to Vietnam] and blow them all to pieces,' they might have been as inclined to vote for him as for a peace candidate. [Voters] were looking for a change."

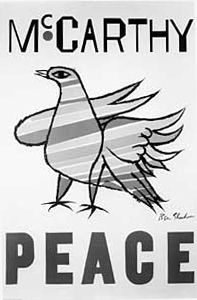

Eugene McCarthy's campaign was associated with the movement for peace.

Courtesy the University of Minnesota

Vietnam had certainly damaged the president's popularity. But Johnson's dismally low approval rating - 38 percent in October 1967 - had as much to do with his handling of summer race riots in Newark and Detroit and the deteriorating condition of the national economy.

After New Hampshire, Eugene McCarthy began to believe he might actually be able to win the presidency. Campaign money and political support began arriving. But so did a formidable new opponent - Robert F. Kennedy. The Democratic senator from New York announced his bid for the nomination three days after the New Hampshire primary.

While McCarthy supporters were elated by the New Hampshire outcome, some began to recognize their candidate's shortcomings. On one hand, McCarthy certainly looked presidential; he was tall, dignified and poised. But for supporters who yearned for a champion whose ardor matched their own, McCarthy on the stump could seem like flat champagne - he had the right flavor but not enough fizz.

The Minnesota senator had a quick but subtle wit - his jokes often came at the expense of others.

A poet and former college professor, McCarthy had a habit of using ten-dollar words to make a ten-cent point. He had a habit of quoting obscure literary figures. Some supporters grumbled that McCarthy seemed to go out of his way to give dull speeches. One activist described a New Hampshire speech this way: "[McCarthy] got a standing ovation when he came in and no one stood when he left."

For two weeks in March of 1968, Kennedy and McCarthy battled for the position of best Democrat to challenge a politically-wounded president. The question was: Would this pair of renegades fatally divide their own party by assailing its incumbent? Lyndon Johnson had an answer of his own.

Lyndon Johnson announces he will not seek reelection in 1968.

Video courtesy MCAmericanPresident

Wisconsin was the next primary state. It would vote on April 2. Sensing defeat, Johnson surprised the nation on March 31 with a startling announcement. In fact, his televised speech contained three big headlines at once: his administration would cease most of the bombing of North Vietnam (which was unpopular in the U.S. and abroad); the U.S. was ready to negotiate a withdrawal from South Vietnam; and Johnson would not run for reelection.

By staying out of the race, Johnson said, he could better concentrate his political authority on achieving peace in Vietnam. He also deprived the opponents from his own party - especially McCarthy - of the primary reason they got into the race: ending the war.

McCarthy's campaign shambled on against the better-known, more organized and enormously charismatic Kennedy (whom McCarthy privately despised). By June 6, when Kennedy died in California, Humphrey was in the race and McCarthy's hopes for the nomination had all but vanished. McCarthy suspended his campaign immediately after Kennedy's assassination. Some say it never really resumed.

At the volatile Democratic convention in Chicago, McCarthy remained aloof from the fray and from his supporters. After Humphrey won the nomination, McCarthy waited until late in the campaign to endorse his friend, mentor and fellow Minnesotan (Humphrey's prolonged inability to break from Johnson on Vietnam was an obstacle). Some bitter Democrats later complained that McCarthy's behavior helped fracture the Democratic Party, contributing to Humphrey's defeat - an assertion that McCarthy and some of his admirers challenged.

Eugene McCarthy retired from the U.S. Senate in 1970. For the next 35 years he wrote poetry, memoirs and political analysis. He ran for president four more times as an independent.

In his final years, some regarded McCarthy as an increasingly eccentric and irrelevant figure. Others saw him as an American original: An independent, reform-minded character whose political skills and intellectual firepower made him a distinctive figure in the nation's public life. No one could deny that Eugene McCarthy forced a failing president from office and thereby changed the course of American history.

Return to Campaign '68