A podcast from APM Reports and the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 just months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were forced from their homes on the West Coast and sent to one of ten “relocation” camps, where they were imprisoned behind barbed wire for the length of the war. Two-thirds of them were American citizens.

Order 9066 chronicles the history of this incarceration through vivid, first-person accounts of those who lived through it. The series explores how this shocking violation of American democracy came to pass, and its legacy in the present.

Sab Shimono and Pat Suzuki, veteran actors and stage performers who were both incarcerated at the Amache camp in Colorado, narrate the episodes. The series covers the racist atmosphere of the time, the camps’ makeshift living quarters and the extraordinary ways people adapted; the fierce patriotism many Japanese Americans continued to feel and the ways they were divided against each other as they were forced to answer questions of loyalty; the movement for redress that eventually led to a formal apology from the US government, and much more.

Sab Shimono and Pat Suzuki, veteran actors and stage performers who were both incarcerated at the Amache camp in Colorado, narrate the episodes. The series covers the racist atmosphere of the time, the camps’ makeshift living quarters and the extraordinary ways people adapted; the fierce patriotism many Japanese Americans continued to feel and the ways they were divided against each other as they were forced to answer questions of loyalty; the movement for redress that eventually led to a formal apology from the US government, and much more.

EPISODES

CHAPTER 1

Japanese warplanes bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Hours later, the FBI began rounding up people of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast. This episode explores the history of anti-Asian prejudice in the United States that laid the groundwork for an assault on Japanese American communities after Pearl Harbor.

BONUS

Order 9066 co-host Sab Shimono's family was incarcerated during WWII. He shares childhood memories of living behind barbed wire.

CHAPTER 2

After Pearl Harbor, pressure grew to forcibly relocate all persons of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific coast. This episode tells the story behind FDR's decision to sign Order 9066, and Japanese Americans recall the painful process of leaving their lives and belongings — and even their family pets — behind.

BONUS

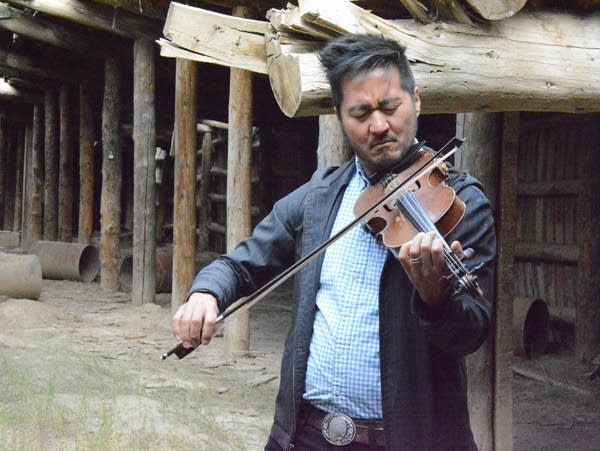

Musicians Julian Saporiti and Erin Aoyama perform songs about the incarceration in a former barrack at Heart Mountain in Wyoming. With a special appearance from Kishi Bashi.

CHAPTER 3

In the first months of incarceration, Japanese Americans were hit with the humiliating conditions of camp life. The U.S. government denied that people of Japanese ancestry living in the "assembly centers" were prisoners, but the first summer in these camps proved otherwise.

BONUS

Kishi Bashi, the renowned alt-rock musician, has been improvising music in places connected to the Japanese American incarceration. That includes the top of Heart Mountain, in Wyoming. Hear Kishi Bashi climb the mountain and perform a song that is part of his "songfilm" project, Omoiyari.

CHAPTER 4

It was a time to persevere in the face of the unendurable, and to do so with dignity. The Japanese term for that is Gaman. This episode explores the ways people in the camps practiced gaman: through work, school, and simply making do.

CHAPTER 5

More than 33,000 Japanese American men and women served in World War II. They fought as soldiers in Europe, and as translators in the Pacific.

CHAPTER 6

In this chapter: the Japanese Americans who protested their incarceration and defied the pressure to prove their patriotism.

BONUS

Two men who were imprisoned at Heart Mountain as boys remember their time in camp and how the experience shaped them as adults.

CHAPTER 7

At the end of 1944, the U.S. government lifted the order barring people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. Many people freed from camp faced racism and poverty as they tried to rebuild their lives. Some found that leaving camp was even harder than being sent there.

CHAPTER 8

Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War Two demand that the federal government take account of their suffering and make reparations.

NARRATORS

Pat Suzuki

Sab Shimono

Pat Suzuki

Sab Shimono

EDITORS

Mary Beth Kirchner

Chris Julin

Mary Beth Kirchner

Chris Julin

THEME MUSIC

Genji Siraisi

Genji Siraisi

AUDIO MIX

Michael Osborne

Corey Schreppel

Veronica Rodriguez

Stephen Smith

Michael Osborne

Corey Schreppel

Veronica Rodriguez

Stephen Smith

SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY PRODUCTION TEAM: John Gray, Jennifer Jones, Noriko Sanefuji, Valeska Hilbig.

APM REPORTS PRODUCTION TEAM: Mike Reszler, Nathan Tobey, Chris Worthington, Alex Baumhardt, Hana Maruyama, Emerald O'Brien, Shelly Langford, Andy Kruse, Mike Mulcahy, Eric Ringham.

ADDITIONAL MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions: Turning to You, Denzel Sprak, Collingwood, Cicle Deserrat, Kalsted, Setting Pace, The Records, Toothless Slope, Lonely Stairwell, Clay Pawnshop, Ervira, Svela Tal, Drone Pine, Vulcan Street, Thread of Clouds, Arabic Tallow, Tessalit, An Accumulation, Intermezzo, Last Lights, Gullwing Sailor, Heather Transit Alias; Kai Engel: Cold War Echo; Poddington Bear: Degradation, Lens Flare, Minor Islands.

SPECIAL THANKS: Densho — The Japanese American Legacy Project.

Support for Order 9066 comes from the Terasaki Family Foundation, the Henry Luce Foundation, the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, and Penelope Scialla.

RESOURCES

Digital Collections

- Densho Digital Repository

- Japanese American National Museum

- Hirahara Photo Collection of Heart Mountain

- Japanese American Archival Collection at Sacramento State University Library

- Go For Broke Oral History Collection

- Dorothea Lange Photo Collection

- Densho Encyclopedia

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History's Righting a Wrong

- 50 Objects 50 Stories

- Manzanar Committee

- Manzanar

- Topaz Museum

- Heart Mountain

- Japanese American National Museum

- McGehee WWII Japanese-American Internment Museum

- Japanese American Museum of San Jose

- Pilgrimage

- A Flicker in Eternity

- Passing Poston

- The Legacy of Heart Mountain

- Scapegoat Cities

- The No No Boy Project

- Omoiyari: A Songfilm by Kishi Bashi

- Life after Manzanar

- Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II (from the Japanese American Citizens League)

- The Language of Incarceration

- Densho: On Terminology

RADIO SPECIALS

In July 2018, Order 9066 was distributed to public radio stations nationwide and heard as a three-part series.

0:00 | 00:52:59

0:00 | 00:52:59

0:00 | 00:52:59

SUBMITTED OBJECTS

Submitted by: Alisa Lynch

In the Manzanar National Historic Site museum collection, we preserve a simple wicker basket with two yellowed paper tags attached. It measures 27.5 cm high by 40 cm long by 24 cm wide. It's a tangible object that can be seen, held, opened, and smelled. No doubt it's like thousands of other baskets of similar size and function.

The basket's stories are what matter most. A young woman named Eiko Yamada carried it from Tokyo, Japan in the 1920s. She journeyed with her baby Lily to join her husband Tamizo who was running a nursey in West Los Angeles. Her heirloom wedding kimono was in the basket. Two decades later, in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Eiko feared that her kimono would be confiscated if the FBI came to search the Yamada's house. She cut the kimono up and lined the basket with its strips of silk. When she and her family were forced into Manzanar, she took the basket with her, attaching paper tags with her assigned family number, 2811. She kept it for the rest of her life.

In the Manzanar National Historic Site museum collection, we preserve a simple wicker basket with two yellowed paper tags attached. It measures 27.5 cm high by 40 cm long by 24 cm wide. It's a tangible object that can be seen, held, opened, and smelled. No doubt it's like thousands of other baskets of similar size and function.

The basket's stories are what matter most. A young woman named Eiko Yamada carried it from Tokyo, Japan in the 1920s. She journeyed with her baby Lily to join her husband Tamizo who was running a nursey in West Los Angeles. Her heirloom wedding kimono was in the basket. Two decades later, in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Eiko feared that her kimono would be confiscated if the FBI came to search the Yamada's house. She cut the kimono up and lined the basket with its strips of silk. When she and her family were forced into Manzanar, she took the basket with her, attaching paper tags with her assigned family number, 2811. She kept it for the rest of her life.

Submitted by: Ken Tsukada

This is a letter from Colorado's Governor Ralph Carr offering a job to Wakako Domoto as a "domestic" in his home in Denver during the war.

Wakako Domoto was my aunt who was incarcerated with my mother and my relatives in the Amache relocation camp. There are several letters from the Carr family inviting Wak to visit after the war. Governor Carr was a "lone" politician who protested the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war.

This is a letter from Colorado's Governor Ralph Carr offering a job to Wakako Domoto as a "domestic" in his home in Denver during the war.

Wakako Domoto was my aunt who was incarcerated with my mother and my relatives in the Amache relocation camp. There are several letters from the Carr family inviting Wak to visit after the war. Governor Carr was a "lone" politician who protested the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war.

Submitted by: Ken Tsukada

This "flow chart" was produced in Granada (Amache camp). It shows the different options to incarcerated Japanese Americans and the potential outcomes.

The chart was in my mother's documents from the time she spent at Amache. I have never seen anything like it. I assume it was produced at camp as the only silk screen operation for the relocation camps resided in Granada.

This "flow chart" was produced in Granada (Amache camp). It shows the different options to incarcerated Japanese Americans and the potential outcomes.

The chart was in my mother's documents from the time she spent at Amache. I have never seen anything like it. I assume it was produced at camp as the only silk screen operation for the relocation camps resided in Granada.

Submitted by: Sam Mihara

A braille board for Japanese-speaking blind people.

When my father was forced into the Heart Mountain camp, he had glaucoma. He was being treated before the war by an eye specialist in San Francisco. But once at camp, there were no such specialists in the camp and the government would not allow him to visit his doctor on the west coast. So I watched as he went totally blind inside the camp. In spite of his handicap, he created a braille system for the blind in Japanese letters with the help of a local craftsman. The board has his name, Tokinobu Mihara, as the creator at the bottom. The photo was taken by Delphine Hirasuna.

A braille board for Japanese-speaking blind people.

When my father was forced into the Heart Mountain camp, he had glaucoma. He was being treated before the war by an eye specialist in San Francisco. But once at camp, there were no such specialists in the camp and the government would not allow him to visit his doctor on the west coast. So I watched as he went totally blind inside the camp. In spite of his handicap, he created a braille system for the blind in Japanese letters with the help of a local craftsman. The board has his name, Tokinobu Mihara, as the creator at the bottom. The photo was taken by Delphine Hirasuna.

Submitted by: Rachael Brown

My grandfather, Robert Hosokawa, was interned with his family at Camp Harmony. He had recently graduated from Whitman College, where he worked on the school newspaper, and went on to become a journalist. While in camp, he published an entertaining newspaper called the Camp Harmony Hooey, with content ranging from news and satirical articles to illustrations and cut-out advertisements. We have three remaining copies of the mock-ups for these newspapers. They are a fascinating glimpse into camp life, including the anger, boredom, and humor experienced by the citizens there.

To me, these newspapers remind me of the humor and tenacity of my grandfather, who died in 2014, but they are also important to our family as one of the first examples of his work as a life-long journalist. He was later released from camp under a rule that allowed men who could find jobs away from the American coasts to leave. One of his college professors had sent our inquiries on his behalf and found him a job on a small weekly newspaper in Independence, Missouri. So he and my grandmother, Yoshi Hosokawa, moved from incarceration to Independence, and went on to become a top editor at the Minneapolis Tribune and a journalism professor at the University of Missouri and University of Central Florida. His brother, William Hosokawa, who was also interned at Camp Harmony, became the editor of the Rocky Mountain News. I remember reading the newspaper with my grandfather as a child, and his pointing out examples of good writing or photo choices. Seeing his camp newspapers as an adult, after becoming a journalist myself, remind me of his lessons about the importance of information and communication, and of his ability to turn injustice into an act of creation.

My grandfather, Robert Hosokawa, was interned with his family at Camp Harmony. He had recently graduated from Whitman College, where he worked on the school newspaper, and went on to become a journalist. While in camp, he published an entertaining newspaper called the Camp Harmony Hooey, with content ranging from news and satirical articles to illustrations and cut-out advertisements. We have three remaining copies of the mock-ups for these newspapers. They are a fascinating glimpse into camp life, including the anger, boredom, and humor experienced by the citizens there.

To me, these newspapers remind me of the humor and tenacity of my grandfather, who died in 2014, but they are also important to our family as one of the first examples of his work as a life-long journalist. He was later released from camp under a rule that allowed men who could find jobs away from the American coasts to leave. One of his college professors had sent our inquiries on his behalf and found him a job on a small weekly newspaper in Independence, Missouri. So he and my grandmother, Yoshi Hosokawa, moved from incarceration to Independence, and went on to become a top editor at the Minneapolis Tribune and a journalism professor at the University of Missouri and University of Central Florida. His brother, William Hosokawa, who was also interned at Camp Harmony, became the editor of the Rocky Mountain News. I remember reading the newspaper with my grandfather as a child, and his pointing out examples of good writing or photo choices. Seeing his camp newspapers as an adult, after becoming a journalist myself, remind me of his lessons about the importance of information and communication, and of his ability to turn injustice into an act of creation.

Submitted by: Dennis Kato

My mother when incarcerated at Amache, embroidered her family's and friends' signatures on a blouse.

I think this is very typical of many Japanese Americans - trying to make the best of a bad situation. By embroidering the signatures, she had a permanent record of those who shared her experience at Amache. She kept it as a treasured keepsake and passed it on to me (her son).

My mother when incarcerated at Amache, embroidered her family's and friends' signatures on a blouse.

I think this is very typical of many Japanese Americans - trying to make the best of a bad situation. By embroidering the signatures, she had a permanent record of those who shared her experience at Amache. She kept it as a treasured keepsake and passed it on to me (her son).

Submitted by: Alan Oiye

A watercolor painting that my father (Shigenori Oiye) painted while incarcerated in Tule Lake and has poetry written by other incarcerees (at least this is what I am told the writing is because I cannot read Japanese).

This is one of six paintings that I have that my father painted. He passed away in 1987 and did not otherwise talk about his experience in Tule Lake.

A watercolor painting that my father (Shigenori Oiye) painted while incarcerated in Tule Lake and has poetry written by other incarcerees (at least this is what I am told the writing is because I cannot read Japanese).

This is one of six paintings that I have that my father painted. He passed away in 1987 and did not otherwise talk about his experience in Tule Lake.

Submitted by: Garrett Nagaishi

A photo of my grandparents' wedding day in Manzanar.

They were married in January 1943, not a year after arriving in the camp. While the photo testifies of the resiliency of those incarcerated during WWII, we must not forget their very real struggles and the long-lasting effects incarceration had on these individuals and their families and friends. I am a direct byproduct of those who were sent to the camps, and I am constantly learning more about my identity.

A photo of my grandparents' wedding day in Manzanar.

They were married in January 1943, not a year after arriving in the camp. While the photo testifies of the resiliency of those incarcerated during WWII, we must not forget their very real struggles and the long-lasting effects incarceration had on these individuals and their families and friends. I am a direct byproduct of those who were sent to the camps, and I am constantly learning more about my identity.

Submitted by: Ron Mori

My mom gave me an iron wood carving from Poston 2 Camp. She and her step father went to an arts and craft camp show and her step father bought it for her.

The wood sculpture was in my grandmother's bedroom in Ca., when we would visit as kids I would sleep under it. It would scare my older brother, but I always liked it for some reason. Later I learned it's a mythical figure for a good harvest. How appropriate as my mother's family were farmers in Costa Mesa, Irvine and Huntington Beach.

My mom gave me an iron wood carving from Poston 2 Camp. She and her step father went to an arts and craft camp show and her step father bought it for her.

The wood sculpture was in my grandmother's bedroom in Ca., when we would visit as kids I would sleep under it. It would scare my older brother, but I always liked it for some reason. Later I learned it's a mythical figure for a good harvest. How appropriate as my mother's family were farmers in Costa Mesa, Irvine and Huntington Beach.