John C. Goodwin was 19 years old when he began to think of himself as a "concerned" photographer-a photographer who wanted to use his craft as a way to improve social conditions. The year was 1966 and Goodwin, whose father was an American Baptist pastor who preached human rights and tolerance from his New Jersey pulpit, felt compelled to speak out against the war in Vietnam. Fresh out of a two-year stint of domestic service in the U.S. Army, Goodwin was moved to action when he attended a meeting in New York City of the Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam (CALCAV). From then on, Goodwin decided, he would use his talent in photography to portray the religious and pacifist dimensions of the peace movement. Over the next several years, Goodwin worked both independently and for religious publications to show the world that hippies and "far out" people were not the only ones concerned with the war; there were activists from religious communities, too. Here Goodwin shares his insight as a documentary photographer during the period in the late 1960s when Martin Luther King Jr. began to speak out against the war in Vietnam, making a connection between the war and the civil rights movement.

April 4, 1967, M.L. King Jr., Riverside Church, NYC (On way to give speech)

On April 4, 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. was invited to speak at an event at the Riverside Church in New York City sponsored by the Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam (CALCAV). Rather than jockeying with other press photographers to find the best spot in the Riverside sanctuary from which to shoot, Goodwin followed King through the hallway as he prepared to deliver the controversial "Beyond Vietnam" speech. "I found it interesting," Goodwin told ARW, "that someone known for his oratory, on the way to the event, was making changes, looking at his notes."

Goodwin's Baptist upbringing helped him get this unique shot of King. He wanted to capture King in the context of the church, and he knew that given the Baptist practice of doing full-body immersion baptisms, there would be enough room in the empty baptismal font behind the podium where he could stand unobtrusively. "I wanted to give the idea of King as the lonely speaker with the congregation laid out before him," Goodwin says. Although Goodwin wishes he'd had a bit more light to show the faces of the people in the congregation, he believes that the darkness enhances the image of King as a "lonely" figure forging ahead with his cause. Goodwin suspects it would be a lot trickier to get these kinds of shots of a high-profile figure in 2008. "By today's standards," Goodwin says, "you'd have police or guards telling you where you could or could not go." But back then, Goodwin was able to roam anywhere he wanted in the church during the speech.

Martin Luther King Jr. talking to the press in the Library of the Riverside Church in New York City after the "Beyond Vietnam" speech, April 4, 1967.

Despite the press hubbub created by King's "Beyond Vietnam" speech, in the immediate aftermath of the event, Goodwin says, all was calm in the library of the Riverside Church. Here you see King speaking to unseen reporters, with CALCAV members--including John Richard Newhouse, standing at the fireplace--casually listening in the background. Goodwin says he didn't have any particular goal in mind with the composition of this shot, but "I was just trying to record the event from whatever angle I could." However, Goodwin says he had the subject's best interest in mind. "Whether I liked them or not, I always tried to come out with a photograph that they would like. I don't want to hold anyone up to ridicule."

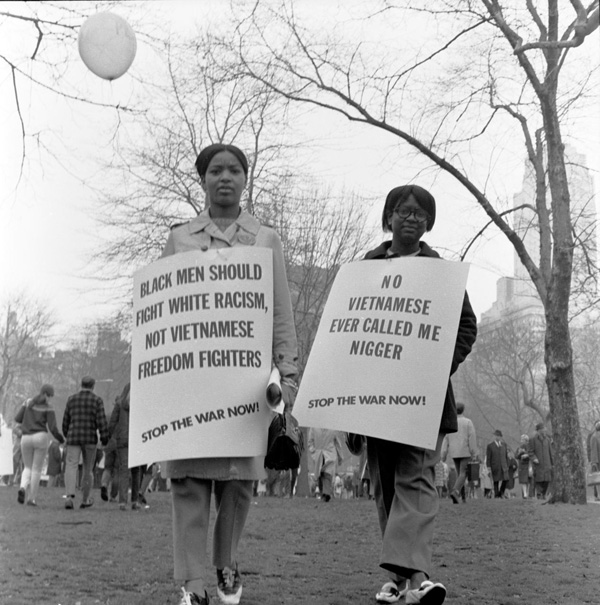

NYC, April 15, NYC, peace march, Central Park

Eleven days after King's "Beyond Vietnam" speech at Riverside Church, Goodwin was assigned to cover a peace march in New York's Central Park for Youth magazine, a publication of the United Church of Christ. After photographing young people who the Youth reporter was interviewing, Goodwin wandered around the park before the march began, trying to "get a sense of it," Goodwin recalls. He came upon these two young women, whose signs bore messages similar to the one he'd heard Dr. King preach at Riverside Church.

King & Spock marching

Noted pediatrician and child-rearing philosopher Dr. Benjamin Spock encouraged Dr. King to join the Peace movement several years before his Riverside Church speech. In 1967, activists encouraged King to run for president as a third-party candidate in the 1968 election with Spock on the ticket. They didn't run, but Spock remained an outspoken anti-war activist and ally of King. According to the Los Angeles Times1, Spock asked an interviewer at the time, "What is the use of physicians like myself trying to help parents bring up children, healthy and happy, to have them killed in such numbers for a cause that is ignoble?" In this image, Dr. King marches arm in arm with Spock and other anti-war protesters from Central Park to the United Nations building in New York City. Goodwin remembers this protest march well because people were throwing bags of flour out of their windows in anger at the marchers, and Goodwin himself was doused in hot coffee sometime after he took this photograph.

1 - "Baby Doctor for the Millions Dies," Los Angeles Times, March 17, 1998

Jan. 12, 1968, CALCAV NYC press conference, William Sloane Coffin Jr., Martin Luther King Jr.

Goodwin caught King in a quiet moment, listening to William Sloane Coffin speak during a CALCAV press conference. This event is significant for Goodwin because it was the first and only time he ever spoke to King. "A news photographer tries to be an invisible person," Goodwin says. "You try to get your photographs like you're a fly on the wall." But he couldn't resist approaching King after the conference since there weren't many people in the room. Goodwin recalls, "I simply said, 'Dr King, I've photographed you many times, we've never talked, but you know my father." And King said, 'Who's your father?'" When Goodwin named the Rev. Dean Goodwin, who knew both King and King's father through Baptist conferences and events, King responded, "Yes I knew your father very well. Please give him my warmest regards."

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Rabbi Abraham Heschel, Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath and Rabbi Everett Gendler in Arlington National Cemetery, February 6, 1968

"In all my life," says Goodwin, "in terms of my photographs, I've thought of photography as reconciling people for the other, reaching across lines of race and gender and helping to make a difference that way." Between 1967 and 1969, CALCAV held annual "Education-Action Mobilizations" in Washington, D.C. for clergy and laypersons from all over the country to converge and put pressure on Congress to end the war in Vietnam. King and Ralph Abernathy, also a Baptist minister, attended the conference on February 6, 1968. In this shot, King and Abernathy are shaking hands with Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath, Rabbi Abraham Heschel and Rabbi Everett Gendler (far right) at Arlington National Cemetery before they led a prayer vigil at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Arlington National Cemetery, L to R: (unknown), Episcopal Reverend Roger Alling, Roman Catholic Bishop James Shannon, (Rev. Richard Neuhaus in 2nd row), Conservative Rabbi Abraham Heschel, Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath, Rabbi Everett Gendler

"I don't think I ever went through a period of being a photographic hobbyist," says Goodwin. "Almost as soon as I started taking photographs, I saw them as a combination of historical and an effort to change the world, change society." When Goodwin shot this photograph of religious leaders of many denominations marching through Arlington National Cemetery in protest of the Vietnam War, he had a sense that this was a historic moment. Goodwin ran ahead of the marchers to get a group shot, and was able to capture this one, epic image of all the leaders of the march. King was assassinated two months later.

Back to Beyond Vietnam.